Chaplains can find themselves in some sticky situations among family members. While our primary focus is often the patient or other person we are working with, we can be brought in to situations where family members are at odds with one another, with staff, or even with the patient. We may be brought in to help defuse a volatile meeting or try and get the family on the same page. The reasons for this often comes down to two of the most important skills we have in our toolbox: our capability of empathy and our ability to listen non-judgmentally. Some people though have a knack of turning those skills against us.

Empathy: the push in and pull out

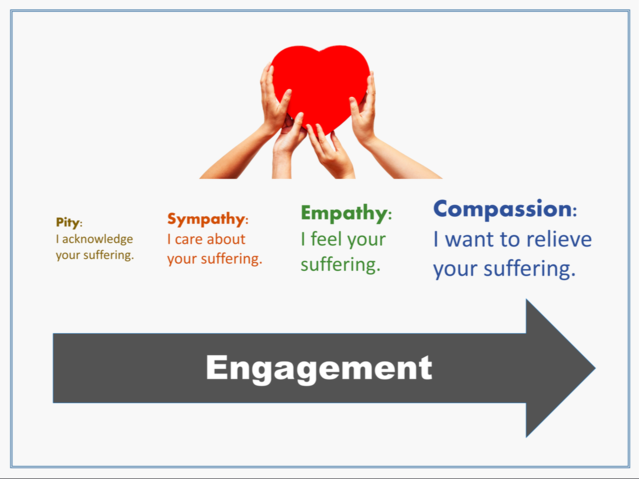

Sympathy and empathy are often used synonymously, but they are different in experience. Sympathy could best be understood as “feeling for”, while empathy could be understood as “feeling with.” I can have sympathy for someone’s sorrow without feeling that sorrow myself. But if I have empathy for someone, I can not only understand someone’s sorrow but feel some of that sorrow myself. A common example is grief: I can sympathize with someone in grief knowing that they are sad and wish to comfort them, but if I have lost someone myself I can better feel the sorrow that someone else feels when they have lost someone.

Empathy is difficult at times though because it can push us in to areas of pain that make us want to fix the situation. Chaplains and other care workers are often drawn to our field because of a sense of compassion. However a good part of chaplaincy training involves identifying where our boundaries are in the helping relationship. Too often caregivers and chaplains can be drawn into situations where they become the rescuer of the other, not only to alleviate the suffering the other is going through but the suffering that they are going through because of the empathetic relationship. Self-awareness of this dynamic is critically important to our role and development as chaplains.

While we may be more aware of individuals who push us to overstep our role, we also need to be aware of those who will push us backward out of our role, moving from empathy to pity (simple awareness of the suffering of others), detachment or even derision. For example I recently had a long conversation with a someone about their loved one who is on hospice. The person I spoke with had a problematic relationship with the rest of her family to the point that she was no longer to receive any information or have any input regarding care. She had been referred to me for grief support as the patient was not expected to last more than a few days and they felt she would not handle the loss well, and had called the office over the weekend wanting my support. However the call quickly became wrapped up in another agenda. The conversation always ended up spinning toward all the problems “out there”: the neglectful staff, the spiteful siblings, the inability of others to see that her over-90-year-old aunt “wasn’t really dying”, she just needed to be on a gluten-free diet.

I tried and tried to remain empathetic and impartial, but after about an hour I felt myself feeling angry and frustrated. I felt that there was little I could do for this person, and was tired of whatever game they were playing. I thought that the base of her anger and frustration was due to grief. What I found though was that the feelings welling up in me were anger and frustration – and I didn’t like it. Not only that, I found myself not liking her because I felt that way. I found myself looking for a door through which I could exit the conversation. I didn’t want to have empathy with her anymore.

And in sitting down later, I see why. The reason? Empathy.

“trust your feelings, Luke”

As I said, what I thought this person was feeling and what they actually were feeling were two different things. I tried to have empathy with her based on how I thought she would – or should – feel, but I found that what I felt – anger and frustration – was more similar to how she actually felt. I was taking on her anger as my own, and putting it back on her. And anger is something I do not deal with well.

It’s a common mistake for chaplains to think they know what someone else is feeling based on prior experience or psychologizing. I realized after the fact that I was trying so hard to figure her out that I wasn’t paying attention to my own empathy with her, which in a way had already “figured her out” as much as I needed to. I was reading her response through the lens of grief: denial, bargaining and anger. But I couldn’t help her see her feelings as part of grief because, in the end, her feelings may have had very little to do with grief. If I had paid more attention to how I felt rather than how I felt she she should feel, I may have reacted differently.

One of the problems I had during the conversation was that my attempts at active listening at times felt ineffectual. I tried saying “you’re frustrated by the situation you’re in” and “it’s understandable to be angry when you’re losing someone you love”, but nothing connected. That added to my frustration. Her confusing and convoluted story made it hard for me to listen. In those situations it’s my tendency to go up in my head and try to figure out what’s going on behind what is being said. It also made me defensive, as I had called this person in order to provide requested counseling only to find that there wasn’t anything I could counsel. I felt this person didn’t even want the kind of help I could provide, only the help I couldn’t provide.

The call ended after over an hour had passed. We went round and round, both of us angry and frustrated with each other I felt. I think it was after the fourth time that I asked “is there anything in particular that I can do to help you?” that she answered “no, I don’t think there is.” Tacitly I agreed. I told her that I had hoped that she had at least felt heard, as she had undoubtedly felt that nobody of importance listened to her, and that if it would help her to talk from time to time just to be heard we could do that.

That may be the most and best I can offer for now.

Hi Sam,

I have read this blog entry a few times and for me it illustrates how verbatims provide a thin, rather than a rich, account of a pastoral encounter. Phone calls are harder because of the information that is filtered out. An important point is whether you called her or she called you, and if she called you whether it was of her own volition or because she was pushed into it. You may have been “set up to fail” if it was in her mind to talk with you just to show someone else that they gave her a bad suggestion.

I placed “set up to fail” in quotes to because I have found that it is also important for a chaplain to understand what they see as success in a pastoral encounter. As Lindsy expressed, listening or sustaining presence was something you provided. The outcome of a pastoral encounter does not only depend on you. While we all like experiences where e.g some healing or spiritual growth occurs I regard success as where a dispassionate observer would say that you were performing your pastoral functions to the best of your skills and knowledge and with the appropriate disposition. I.e. success is process based rather than outcomes based.

Thanks for your comments John. Yes this was difficult to present. I was hoping to use it as an example of how empathy works and how it isn’t always “warm and fuzzy”. Plus I needed to work through the process on my own, which was very beneficial for my own purposes.

She had made the call after several of our staff raised concerns that she may be in need of support. As she had a history of trying to pull information from people I said I might be the best contact as I had no contact with the patient and therefore would have the least to say or offer. I have no idea though what was brought up to her in terms of what “counseling” meant. It felt a bit like she had waited in a long line in the DMV and, after arriving at my window, had no idea what the line was for.

I want to say further that although the encounter was frustrating and aggravating – for both us – I don’t think it was necessarily a failure. I certainly didn’t have the outcome that I expected or hoped for, but I felt I had done the best I could given what was handed to me. I think we all hope to be “effective” but we also need to hold that expectation with an open hand, knowing that it’s not something we can grasp on our own.

Well said about needing boundaries (just because you can empathize doesn’t mean some people aren’t inappropriately expressing themselves and need a kind redirect). Even if she couldn’t feel heard, you still listened – you still were there. You kept offering a connection (that was requested) until you needed to create some boundaries – which is allowing you to be a better chaplain/active listener for the next person you work with. And you still left that connection open, which is actually a big offer.

Thanks very much for your comments. Part of this was simply working out on paper what was going on in my head. It was tough. A big unspoken reason why it was tough was because this was over the phone. I find that when you take away all the visual cues and physical presence from a conversation like this one it becomes extremely difficult to manage at times. Phone calls in general are very hard for me because of that depersonalization. All in all I think she felt heard but she didn’t want to be heard. She wanted an ally in the fight which was something I couldn’t give her.